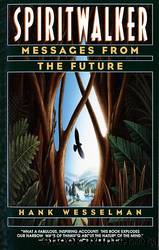

Spiritwalker: Messages from the Future by Hank Wesselman

Author:Hank Wesselman [Wesselman, Hank]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 978-0-307-57399-5

Publisher: Bantam Books

Published: 2012-04-25T04:00:00+00:00

My excitement about my experiences was tempered by caution. My academic colleagues had given a vitriolic reception to Carlos Castanedaâs well-known books about his apprenticeship with a Yaqui Indian sorcerer. Castanedaâs work was steeped in controversy almost from the start, and most professional anthropologists believe he had made up a story and foisted it on the world as the real thing. To the anthropological establishment, the fact that his books became immensely popular and made a lot of money was the kiss of death. One of my professors at Berkeley ranted against Castanedaâs work, calling it cultural anthropologyâs equivalent of the Piltdown man hoax. Perhaps this tirade was due to the professorâs never having experienced an altered state. Harner says that individuals who have the most difficulty in achieving the shamanic state of consciousness tend to be in highly structured, âleft-brainâ professions. My academic colleagues would probably share my own inner professorâs skepticism about my experiences. Most anthropologists have highly trained intellects that become ever more narrowly focused on their specialty areas. Many are completely unaware of the nature of their subconscious and how it functions.

Albert Einstein, it is said, went sailing to relax after intellectually wrestling with a problem that he couldnât quite solve. During his sail a bolt of intuition suddenly showed him the solution. From the Hoâomana perspective, Einsteinâs solution probably originated from his aumakua, came in through his ku, and was received by his lono intellect. The ku, which is gratified by any pleasurable physical activity, must have been delighted at being outdoors, in dynamic association with nature. Under these circumstances Einsteinâs ku responded to his need for information, rewarded him in turn with a momentary expanded state, made contact with his aumakua, which is in touch with the collective informational matrix, and the problemâs solution was revealed.

I could also now see why Nainoa might think that the cross represented the human aumakua in nonordinary reality. Other ancient cultures also use it as a spiritual symbol. At the American Museum of Natural History in New York, for instance, I have seen crosses embroidered on the breast and knees of a Chukchi shamanâs costume. Ethnographic data obtained when the outfit was acquired in Siberia in the 1800s revealed the crosses to be birds, symbolic abstractions of the shamanâs spirit flight into nonordinary reality.3

Even the Neanderthal people may have used the cross as a symbol. A small round stone engraved crudely but definitely with a crossâfrom the site of Tata in Hungary4âhas been dated at fifty thousand years before the present. It is one of the earliest examples of symbolic expression in human evolution. It may mean that the Neanderthals had shamans or that they used the cross as a symbol for an abstract concept. Like the stone monolith, the cross found its way out of the human mind and into the art of most of the worldâs prehistoric cultures.

Viewed from this perspective, the image of Jesus on the cross acquires an entirely new, expanded meaning: a composite symbol of both the spiritual teacher and his aumakua aspect.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Becoming Supernatural by Dr. Joe Dispenza(8223)

Crystal Healing for Women by Mariah K. Lyons(7933)

The Witchcraft of Salem Village by Shirley Jackson(7277)

Inner Engineering: A Yogi's Guide to Joy by Sadhguru(6798)

The Four Agreements by Don Miguel Ruiz(6767)

The Power of Now: A Guide to Spiritual Enlightenment by Eckhart Tolle(5788)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5373)

The Wisdom of Sundays by Oprah Winfrey(5165)

Room 212 by Kate Stewart(5129)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5012)

Fear by Osho(4741)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4721)

Animal Frequency by Melissa Alvarez(4475)

Rising Strong by Brene Brown(4465)

How to Change Your Mind by Michael Pollan(4358)

Sigil Witchery by Laura Tempest Zakroff(4248)

Man and His Symbols by Carl Gustav Jung(4138)

The Art of Happiness by The Dalai Lama(4132)

Real Magic by Dean Radin PhD(4131)